Brief History of Hawaiian Language Education

Prior to the arrival of the first company of Calvinist missionaries in 1820, ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi was solely an oral language. With this understanding and armed with a printing press and hopes of conveying the Gospel printed in Hawaiian for a Hawaiian-reading population, the missionaries got to work on developing a written form of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi. In January of 1822, the first printed piece came off the press and a month later, 500 copies of a 16-page Hawaiian Language speller-primer were ready with a tentative alphabet.

Missionaries first targeted the Aliʻi nui (highest Chiefs), who took quickly to this innovation and the advantages of written correspondence. By 1832, over 23,000 adults were reading and writing in Hawaiian. In 1840, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi shifted its focus to children and established the Ministry of Education with a constitutional mandate for compulsory education for children 15 years and younger—the 5th country in the world to do so, predating America and the majority of Europe . By 1853, the Ministry had over 420 Hawaiian language schools, contributing to an 91-95% Hawaiian language literacy rate amongst the people in the later half of the 19th-century.

During this time, several dozen Hawaiian language newspapers informed, connected, and entertained the Hawaiian reading populace. Topics included current events, cultural practices, original transcriptions of epic oral narratives, and serialization of translated English literary works such as Ivanhoe and The Arabian Nights, and many others.

Following the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in 1893, ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi was marginalized and in 1896, the governing body of the time known as the Republic of Hawaii codified into law that only English would be “the medium and basis of instruction in all public and private schools” essentially banned Hawaiian language from the public school system and by the turn of the century, there were no longer any Hawaiian Language Schools (Section 30, Laws of the Republic of Hawaiʻi, 1896). In 1895, the President of the Board of Education, William Alexander, commented: “The gradual extinction of a Polynesian dialect may be regretted for sentimental reasons, but it is certainly for the interest of the Hawaiians themselves” (Republic of Hawaiʻi–Biennial Report of the Bureau of Public Instruction 1895). The prevailing mindset that speaking the Hawaiian language was not in the best interest of Hawaiians influenced projects, policies, programs, and practice within the Department for most of the 20th century.

As an important note to consider, the last printing of a Hawaiian language newspaper was in 1953. This meant that the avenue for a community of native speakers of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi who were successful at reading and writing would become more and more narrow; this essentially relegated the use of Hawaiian as the language of society to a practice of the past.

Beginnings of Hawaiian Language Immersion Education

The Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1960s and 1970s saw a rise in Hawaiian self-identity manifest in music, political civic engagement, and a resurgence of cultural practices. A few iconic moments include the establishment of the Merrie Monarch Hula Festival (1964), Hōkūleʻa’s journey across the Pacific (1975), the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (1976), and the State Constitutional Convention that established the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) and made Hawaiian an official State language (1978).

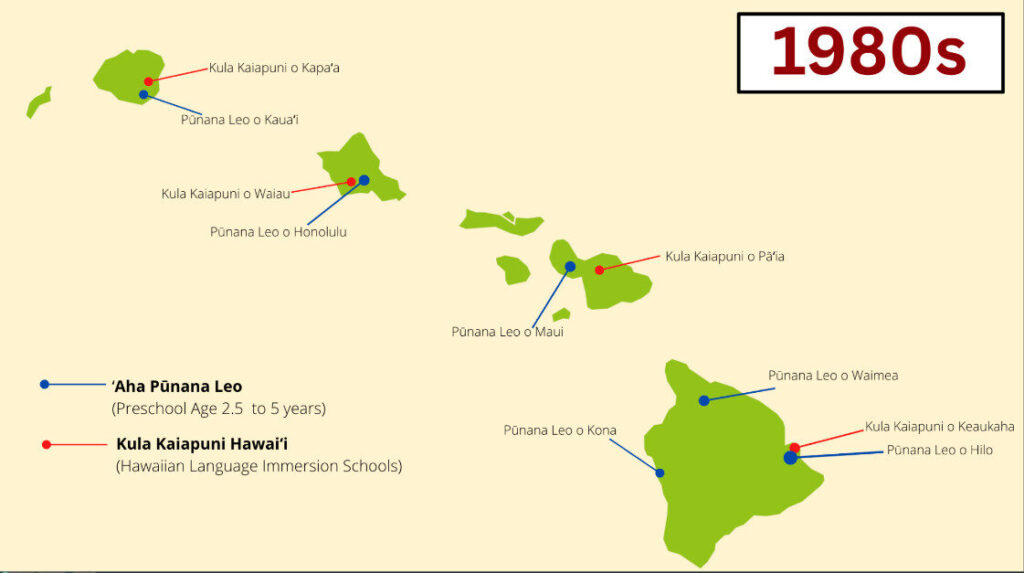

During this time, there were students studying the Hawaiian language at the University of Hawaiʻi who wanted to take the Hawaiian language from a subject of study to one spoken in everyday life. In the early 1980s, this group came across a Māori language immersion preschool program in Aotearoa (New Zealand) called Kōhanga Reo and decided to emulate it by giving birth to the Pūnana Leo movement of Hawaiian language immersion preschools. The first Pūnana Leo preschool opened in 1984 on Kauaʻi, followed in 1985 with a Pūnana Leo in Hilo and Honolulu, and then in 1986 with Pūnana Leo o Maui.

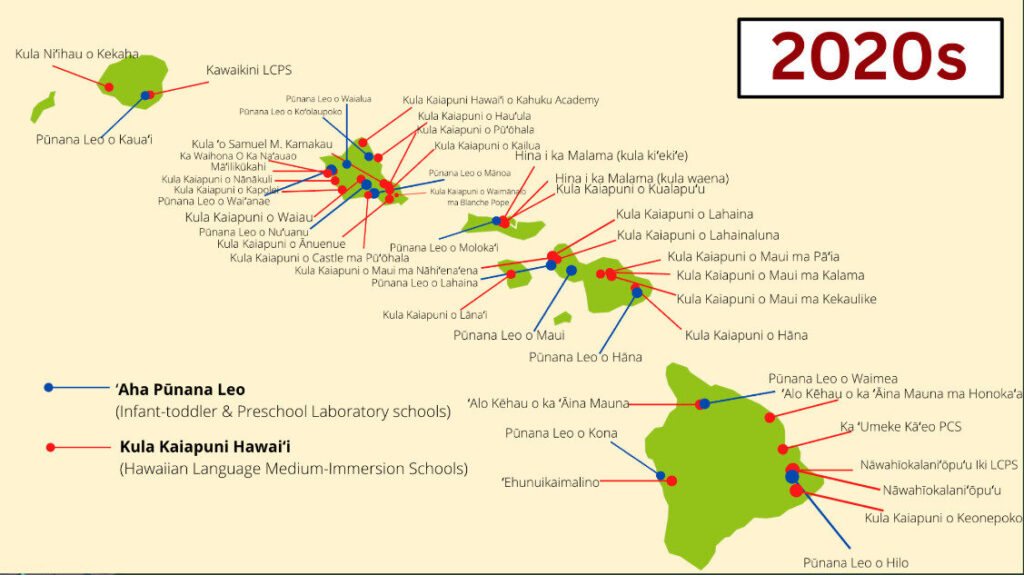

Parents with children in the Pūnana Leo preschools made the conscious decision to seek to establish an avenue for Hawaiian-medium education in the Public Education system rather than end with preschool education. In 1986, these ʻohana lobbied the State Legislature to establish Ka Papahana Kaiapuni in the Hawaiʻi Department of Education. From no Hawaiian language schools in 1900 to two in 1987, Hawaiʻi today has 28 Hawaiian language schools, composed mainly of Kaiapuni Hawaiʻi sites plus public charter schools.

Ka Papahana Kaiapuni Today

In February 2015, the Office of Hawaiian Education (OHE) was established under the Department’s Office of the Superintendent due to a policy audit conducted by the Hawaiʻi State Board of Education (BOE), which recognized that education in Hawaiʻi “should embody Hawaiian values, language, culture and history as a foundation to prepare students in grades K-12 for success in college, career and communities, locally and globally (Hawaiʻi BOE Policy 105-7, 2014). The programs governed by OHE include: E-3 Nā Hopena Aʻo, 105-7 Hawaiian Education, and 105-8 Ka Papahana Kaiapuni.

In SY 2024-25, the Department served 2,452 students enrolled in 22 DOE Kula Kaiapuni on five islands across the State—Hawaiʻi Island, Maui, Lānaʻi, Molokaʻi, and Oʻahu. In addition, there were 1,320 students enrolled in 6 Kaiapuni Hawaiian language immersion charter schools operating on 4 islands—Hawaiʻi Island, Molokaʻi, Oʻahu, and Kauaʻi.

Kaiapuni instruction is delivered exclusively in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, with the introduction of English starting at Grade 5. Students may access Kula Kaiapuni starting in Papa Mālaaʻo (Kindergarten) and may graduate from the program at Grade 12. Students who graduate from Kula Kaiapuni are expected to meet the Board of Education graduation credit requirements (Board of Education Policy 102-15) and in doing so, receive their diploma commensurate with those requirements. Board of Education Policy 105-8 states that “Ka Papahana Kaiapuni (Kaiapuni Educational Program) provides students with Hawaiian bilingual and bicultural education,” and to that end, Kaiapuni graduates have an additional expectation of proficiency in both official languages of the State of Hawaiʻi.

Recently, OHE has taken a broad approach in its work to address capacity building and systems change. The goal is to increase readiness within the Department to take on the more significant task of strategic planning for a high-quality ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi educational experience for Kaiapuni students and families. The focus for OHE’s work related to Kaiapuni education has been to:

- Strengthen the educational infrastructure of Kaiapuni education by advancing a Kaiapuni curricular framework: This work includes identifying and deploying appropriate professional development opportunities for Kaiapuni faculty and administrators, appropriate formative assessment tools for students, and aligning school level instructional strategies with a Kaiapuni curricular framework. More information on the curricular framework can be found in the Foundational and Administrative Framework for Kaiapuni Education (FAFKE) in Attachment B.

- Address needs related to Kaiapuni expansion and demand for reasonable access to Kaiapuni education: This includes activities to support complex areas and schools when there is a request for reasonable access to new and/or existing schools, support new classroom needs, increase the qualified ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi teacher candidate pool and other support services aligned to delivering an ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi education to students enrolled in the program.

Historically, the Department has relied on and commends the long-standing, trailblazing work of external indigenous education leaders and experts here in Hawaiʻi, nationally, and internationally. The Department plans to continue partnerships with those across the University of Hawaiʻi system campuses, researchers, and leaders in Aotearoa, and local and national advocates from various native education groups. In addition, the Department also acknowledges the collective work of organizations such as the ʻAha Pūnana Leo, Native Hawaiian Education Council, the Native Hawaiian Education Association, the Kamehameha Schools, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, and many others in the community who continue to promote value for Kaiapuni education in the Department.

Challenges and Issues

The rapid expansion of Kula Kaiapuni in the early years and the presently increasing demand for access to Kula Kaiapuni has led to many challenges. A primary barrier is a lack of teachers who are qualified to teach in a Kaiapuni classroom and have the Hawaiian language speaking skills to do so. Additionally, Kula Kaiapuni have opened on existing sites that currently operate a primarily English-medium education program or on campuses that have been repurposed, like in the case of Ke Kula Kaiapuni ʻo Ānuenue, which houses a K-12 Kula Kaiapuni on a campus that was originally built for a small elementary school. The assigned facilities were not designed to address the expansion of educational opportunities like having two languages on the same campus or ensuring there are adequate facilities for K-12 expansion within the local complex area. These barriers present challenges that are fueled by increased demand, community will, and the challenges of educating students in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi in an English-only education system.

From SY 1987-88 to SY 2023-24, student enrollment has increased to approximately 3,700 students across all DOE Kula Kaiapuni. As demand increased over time and expansion into new sites occurred, the Department faced challenges in planning for the educational needs of a Hawaiian-language medium education pathway. An investigation into the current systems of support to account for the academic achievement of Kaiapuni students in a second language learning (ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi) environment is necessary to identify appropriate resource needs for learning and teaching in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi and grounded to the knowledge system of Hawaiʻi’s indigenous people.

For over 35 years, families have had the option to enroll their children in Kula Kaiapuni operating on the outskirts of the larger English-medium education system that is the Department. With a firm reliance on leadership for Kaiapuni needs provided by community partners, the Department is still trying to understand how to successfully offer Kaiapuni education with its partners in consideration of federal, state, and Department policies.

In 2014, the Department began testing students in Grades 3 and 4 using the ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi Kaiapuni Assessment of Educational Outcomes (KĀʻEO) to report on student achievement for federal accountability purposes. The KĀʻEO Assessment was expanded in 2017 and students in Grades 3 through 8 are currently being assessed in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi. Issues related to the reporting of KĀʻEO test scores continue to exist and schools have been asking for support to better understand students’ progress and achievement to make informed instructional decisions.

Currently, two (2) teacher preparation programs can directly certify Kaiapuni teachers: the College of Education at UH Mānoa and the Ka Haka ʻUla ʻo Keʻelikōlani – College of Hawaiian Language at UH Hilo. For the last 30 years, the University has worked to build a new field of research related to indigenous education and indigenous immersion education practices. The Department continues to lean on these research-based practices and the practice of active Kaiapuni teachers in the field to strengthen the Ka Papahana Kaiapuni.

Years | Number of Kaiapuni Teacher Vacancies Reported to TATP |

|---|---|

2016 | 27 |

2017 | 31 |

2018 | 40 |

2019 | 51 |

2020 | 48 |

2021 | 46 |

2022 | 75 |

2023 | 52 |

2024 | 51 |

2025 | 56 |

Table 1 (left) provides data collected from Teacher Assignment and Transfer Program (TATP) postings between SY 2016-17 to SY 2024-25. The table shows the amount of teacher positions that were posted in TATP by year. The increase in student enrollment over the same period went from just over 2,400 students to approximately 3,400 students enrolled in Kaiapuni program schools. Finding licensed ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi teachers to meet the increased demand remains a struggle for the Department to find a viable solution to.

To address the teacher shortage, a multi strategy approach was employed to build Kaiapuni teacher recruitment programs. In SY 2017-18, OHE implemented the the Kaiapuni Teacher Permit program called “Palapala Aʻo Kūikawā (PAK)”.

Strategies to Address the Kaiapuni Teacher Shortage

PAK | College Recruitment | Teacher Incentives | Increase ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (in-service) | Recruit ʻŌH teachers (in-service) | Online Kaiapuni Core Classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

• 5 ‘āuna & open enrollment • 30 active permits • 23 licensed | • UHH Kahuawaiola • UHM MEdT • UHM BEd • Grow Our Own – Kaiapuni • UHM BAM • UHMC Hoapili Pathways | • Appropriate compensation (BOE 105-8) • Kaiapuni teacher differentials • Federal Shortage Designation • Housing | • Offer Hawaiian language courses to licensed teachers in various content areas • Add a field Kaiapuni | Encourage teachers to apply for vacant Kaiapuni teaching positions during TATP. | • Cross-listing students in E-school courses • Availability of curriculum resources • Dual Credit & Credit Recovery |

Approved Hawaiian Permits by school year

PAK was designed to make visible any uncertified Kaiapuni classroom teaching staff, many who had been working in various substitute teaching and classified staff roles, to put them in a pathway to licensure. The HSTB reports the data for PAK permits and can be seen below.

2019-2020 | 2020-2021 | 2021-2022 | 2022-2023 | 2023-2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

8 | 6 | 7 | 20 | 29 |